Further Practical Techniques

This lesson covers:

- Heating reactions using reflux and distillation

- Filtering solids under reduced pressure

- Purifying organic solids by recrystallisation

- Choosing appropriate recrystallisation solvents

- Using melting points to assess purity

Heating is often required for organic reactions

Organic reactions can be slow to occur. Moreover, many organic compounds are both flammable and volatile. Heating reactions in an open vessel often results in the loss of reagents before the reaction can progress significantly.

Two essential techniques, reflux and distillation, help overcome this issue.

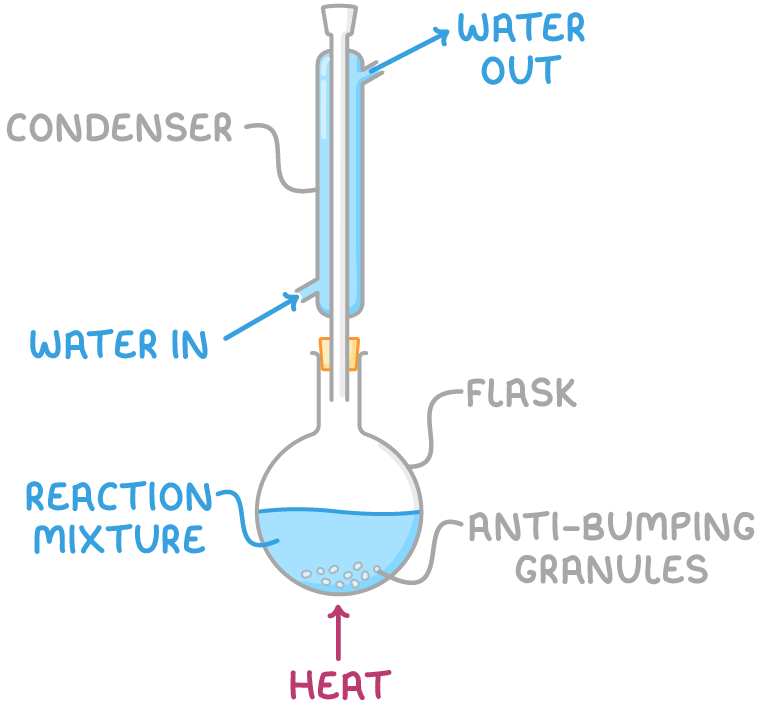

1. Reflux

- Involves heating the reaction mixture in a round-bottomed flask equipped with a Liebig condenser.

- As the mixture boils, vapours condense in the condenser and return to the flask, preventing the escape of reagents.

- However, a drawback of reflux is that desired products may undergo further reactions if heated for too long.

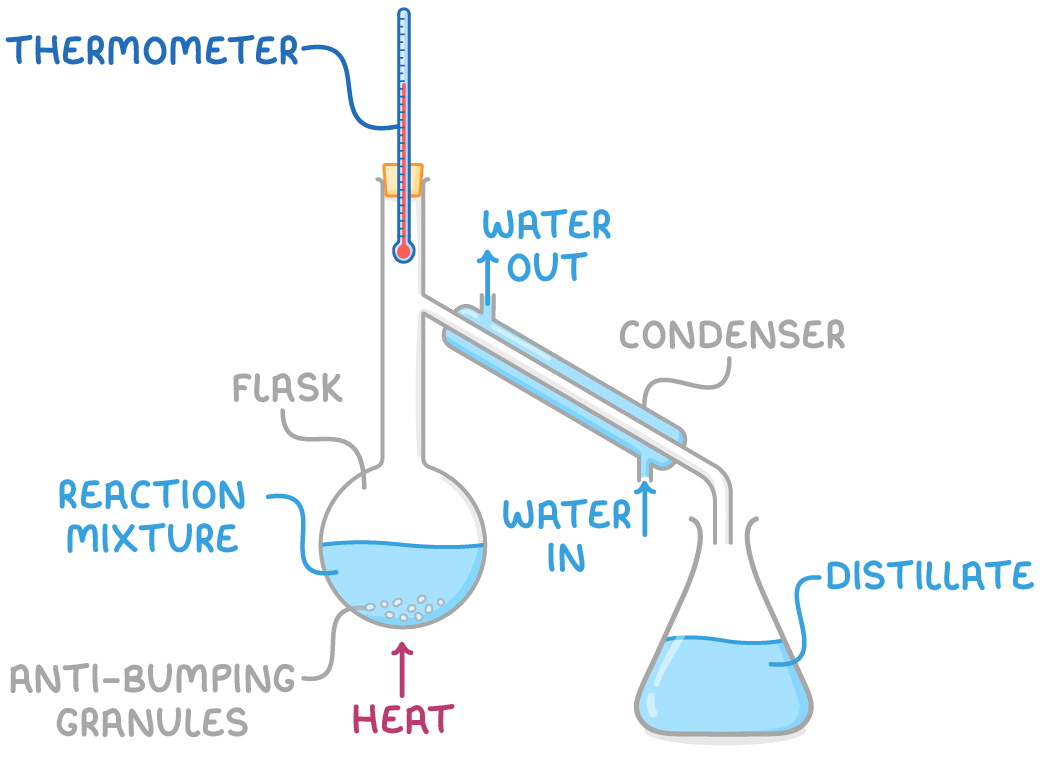

2. Distillation

- Involves gently heating the mixture so that components evaporate according to their boiling points.

- This is particularly useful if the desired product has the lowest boiling point, allowing it to be selectively evaporated and condensed, thereby avoiding unwanted side reactions.

- Distillation is most effective when the product's boiling point is lower than that of the reactants.

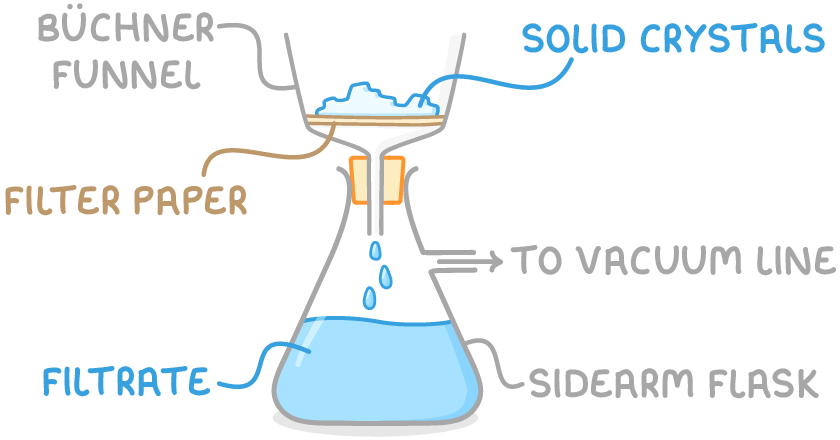

Filtering solids under reduced pressure

Filtration under reduced pressure is a technique for separating a solid product from liquid impurities in a reaction mixture.

The steps for filtering an organic solid under reduced pressure are:

- Transfer the reaction mixture into a Büchner funnel with a piece of filter paper. The funnel is positioned on top of a flask connected to a vacuum line.

- Apply suction to quickly draw the liquid through the filter, leaving the dry solid on the filter paper while the filtrate containing liquid impurities is collected in the flask below.

This method is frequently used to isolate crystals obtained from recrystallisation.

Recrystallisation purifies organic solids

Recrystallisation is a technique for purifying organic solids.

The steps involved in recrystallising an impure organic solid are:

- Dissolve the impure solid in a minimal amount of hot solvent to create a saturated solution.

- Allow the solution to cool slowly, which encourages the formation of pure crystals while impurities remain in the solution.

- Filter the mixture under reduced pressure to collect the crystals, and wash them with a small amount of cold solvent to remove any residual impurities on the crystal surface.

- Dry the purified crystals.

This method exploits the principle that solubility typically decreases with temperature, allowing the pure product to crystalise while more soluble impurities remain in the solution.

Choosing a suitable recrystallisation solvent

The ideal recrystallisation solvent should:

- Fully dissolve the solid at high temperatures.

- Promote crystallisation of the solid as the solution cools.

This ensures that:

- The maximum amount of product crystallises upon cooling.

- Impurities stay dissolved in the solution.

If solubility is too low when hot:

- The product does not fully dissolve, even upon boiling.

- This prevents recrystallisation since crystals cannot form from a solution.

If solubility is too high when cold:

- The product remains dissolved in the cold solution.

- Crystals fail to form, leading to product loss during filtration rather than impurity removal.

Melting points indicate purity

The melting point of a compound is a valuable indicator of its purity. Pure substances melt at precise temperatures, while impure substances melt over a range of temperatures.

To accurately determine the melting point of an organic solid:

- Place a small quantity of the solid into a capillary tube, ensuring it falls to the bottom.

- Place the tube in an oil bath and gradually heat it while continuously stirring the bath to maintain even heating. Monitor the temperature using a precise thermometer.

- Record the melting point range of the solid, noting the temperatures at which the solid starts to melt and when it has completely melted.

- Repeat the process (steps 1-3) to confirm the accuracy of the melting point range obtained.

Comparing the observed melting point range with known literature values helps assess the purity of the organic solid. A narrow melting point range (1-2°C) that closely matches the literature value suggests high purity. In contrast, a wider range or a melting point that is significantly lower than the literature value indicates the presence of impurities.